Although the overall value of housing finance lending dropped by about 30 per cent after the onset of the crisis in early 2008, this was much less than in other developed markets such as the UK and the US. In those markets housing finance effectively stopped dead in its tracks, as the capital markets froze and financial institutions fought for survival. It is also now well known that dwelling values in those markets experienced material declines over the next few years – in some parts of the US up to 50 per cent from the peak.

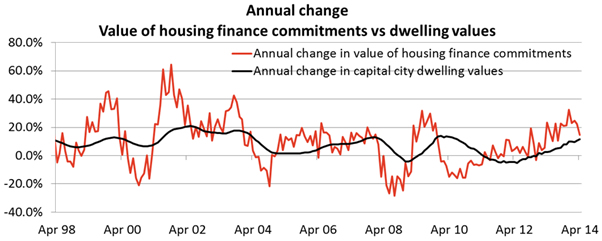

This experience highlights the importance of the availability of housing finance to support home values. The graph below highlights the close correlation between the two.

Before exploring the graph, let’s first understand the macro numbers.

Australia has about 9.5 million homes currently valued at roughly $5.5 trillion.

Just over half of these homes, 5 million to be precise, have a mortgage on them. The aggregate value of the outstanding housing finance is ~$1.3 trillion, meaning the aggregate LVR for the country is roughly 25 per cent.

Whilst this isn’t a material level of leverage, it doesn’t really highlight the importance of the continued availability of housing finance to Australia’s home values.

In 2013 approximately 1 million new home loans were made for a total value of $300 billion. In 2008 that number was much closer to $200 billion, as financial institutions tightened their credit criteria.

The graph below highlights this material decline in the value of housing finance commitments at the start of 2008 and then the marked increase in 2009 in the aggregate value of housing finance commitments off the back of government stimulus, the Reserve Bank lowering the cash rate to emergency low levels and the federal government materially increasing grants to first home buyers.

What can be seen though is the marked correlation between the value of housing finance commitments and the annual change in capital city values, albeit with a lag of a few months.

This makes sense. If people are unable to borrow, or unable to borrow as much due to banks restricting credit due to funding constraints, then consumers aren’t in a position to extend themselves as much when purchasing property.

At the same time, overly exuberant credit growth can lead to a short-term, and ultimately unsustainable growth in home values. In the long run you would expect both credit growth and dwelling value growth to each broadly approximate the growth in incomes.

So when people next complain about the profitability of the banks, think about the importance of the banks continuing to lend money against residential property in order to preserve and grow the value of Australia’s largest and most valuable asset class.