He wanted to know whether anything could make the chickens more productive so they would lay more eggs. Chickens, like human beings, are social creatures; they live in groups. The simple but elegant experiment William devised is described by entrepreneur Margaret Heffernan in her TED talk. Purdue selected an average flock and left them alone for six generations – this was the control group. The second group was created by taking only the most productive individual chickens or ‘super-chickens’ to create a super-flock and only the best were used for breeding.

After six generations had passed, the average chickens were doing well. They were plump, fully feathered and egg production had improved dramatically. In the super-chicken flock only three were still alive – the rest had been pecked to death by the most super of the super-chickens. Even three brilliant chickens can’t possibly lay the eggs of a plump, healthy flock. It turns out that the individually productive chickens had only achieved their success by suppressing the productivity of the rest.

What Purdue did was the chicken equivalent of the most popular way we currently manage teams for higher productivity and performance – we seek to recruit talent or super-chickens.

The super chicken approach to performance

It’s a logical approach; if we want to improve team performance then we simply improve the calibre of the individual members of the team, instil a little healthy competition and reward high achievement.

Ever since McKinsey & Co proposed that successful businesses were always engaged in a ‘war for talent’ in the 1990s, we’ve been obsessed with finding and keeping these super-chickens. Today, companies like AT&T, Pfizer, Cisco and Deloitte’s all have a chief talent officer on the payroll. Even governments are taking the talent solution seriously. The Chinese, South Korean and Singapore governments have all started nationwide talent strategies to ensure long-term performance and competitiveness.

Despite the hype, most of us have had the experience of recruiting a super-chicken or being in a team and having one strut their stuff, only for that individual to never quite live up to the hype or expectation. Often it’s a disaster and those at the top are left confused. Why is the super-chicken not producing the results they were recruited on the back of? Meanwhile, those in the team are left irritated, alienated and disengaged. Not only does this approach put unachievable expectations on the super-chickens to deliver something next to impossible without the active and willing participation of the rest of the team, but it vastly underestimates the potential of the team and massively insults their value and contribution. Hardly a recipe for high team performance!

Most of us are not very motivated by pecking orders or by super-chickens and superstars, and yet we’ve run most organisations and some societies using this model. We've thought that success is achieved by picking the brightest, most talented people in the room, giving them all the resources, all the power and letting them weave their magic. But it just doesn’t work. In fact, most of the time the results mimic William Muir's experiment: aggression, dysfunction and waste. If the only way the most productive can be successful is by suppressing the productivity of the rest, then it’s little wonder we never seem to elevate performance over the long term.

Focusing on talent is unreliable at best and actively destructive at worst because it doesn’t take personality, and therefore fit, into account.

‘Fit’ is the only effective way to manage a team for high performance

‘Fit’ is much, much more important than what we currently consider as talent. In fact, I would argue that talent is simply the misdiagnosis of ‘fit’. Talent is not some elusive divine spark that only the few possess, but rather consistent output made possible when an individual understands their natural strengths, characteristics, skill set and values, and then matches them to a role and environment that needs and values those attributes.

Star performance is not so much about what you do (which incidentally is what almost all performance improvement programs focus on), but rather how you do what you do, why you do what you do and where you do what you do. In fact the only important consideration regarding what you do is what you do to screw things up.

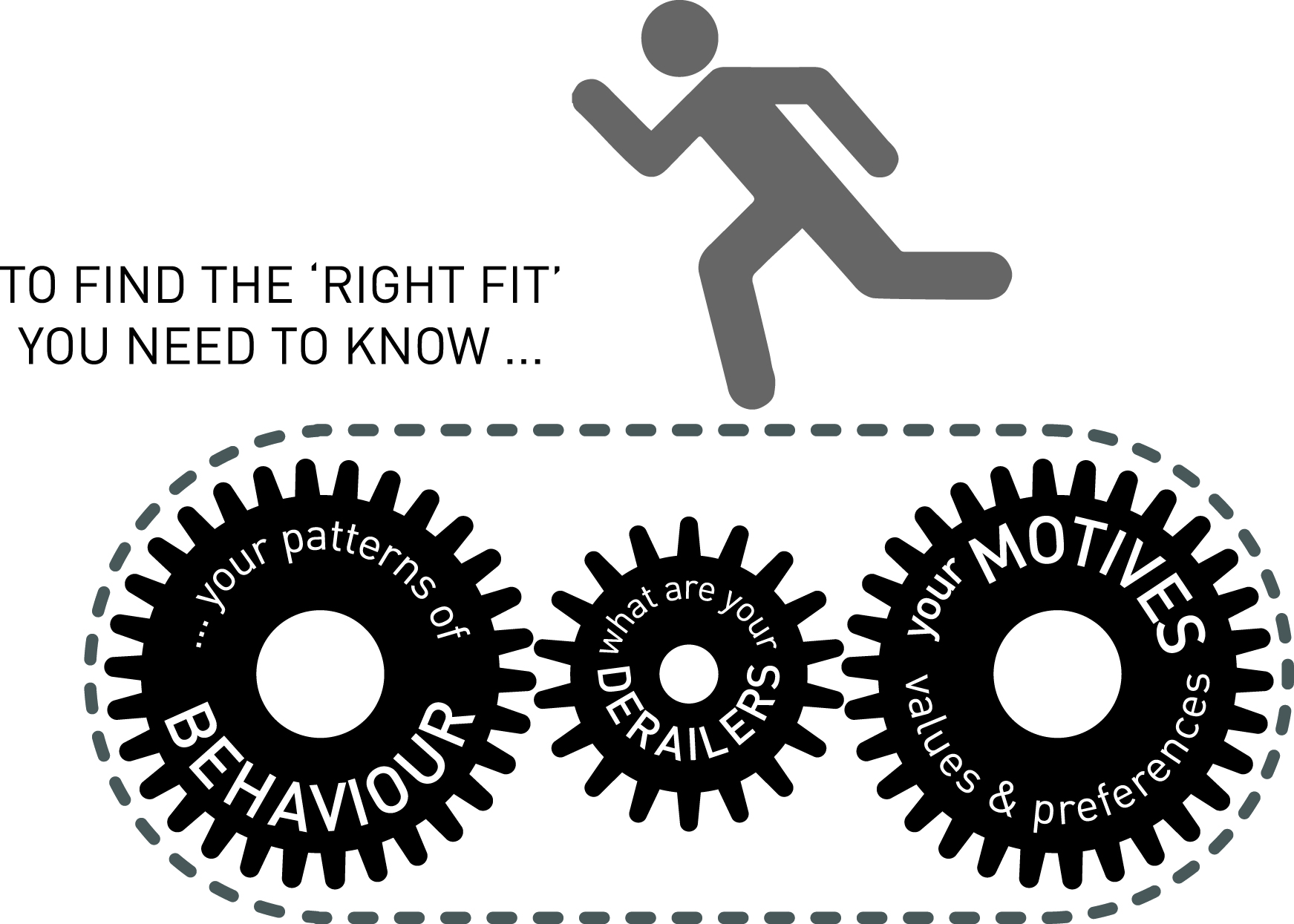

Figure 1.1: The three components of fit

When we understand what motivates us from the ‘inside’, understand our ‘bright side’ behaviours or what we are best suited to, our ‘dark side’ derailers or how we sabotaged our own performance, then we can make sure we are in the right place doing the right thing in the right team or organisation for us. We can make sure we fit.

The reason high performance is so mysterious and inconsistent for so many people is because we are almost solely focused on improving behaviour or the skills, knowledge and experience that an individual brings to a team. As a result, we completely dismiss the impact of personality on individual and team performance.

What I have found across over 3,000 profiles of elite performers in business is that they all have four or five behaviours that evolve as a result of their unique personality – and they use those same behaviours consistently. The only difference between brilliant and average performance is that the average performers are not consciously aware of exactly what those behaviours are so they are either deployed inconsistently or deployed in a role or environment that doesn’t need or value those particular behaviours. The star performers on the other hand know what their bespoke behaviours are, or they simply deploy them innately at the right time and in the right place most of the time.

If you understand the quirks of your personality you can make little, almost imperceptible shifts that ensure you are in the right place doing the right things which collectively can have a profound impact on performance.

Do that for an entire team and you don’t need to find and keep expensive, often difficult to manage super-chickens. Instead, simply allow the individual team members to swap tasks and responsibilities to ensure more are doing what comes naturally to them, thus allowing them to deploy their ‘bright side’ behaviours most of the time and enabling you to create a plump, healthy team where productivity soars.