On 1 November, the RBA left the official cash rate unchanged at its record-low level of 1.50 per cent. While some analysts had forecast a rate cut to 1.25 per cent at the November RBA board meeting, there was also the expectation that any cut in November would have been the last, as too low a rate could encourage people to take on more debt.

Delivering a speech at the Committee for Economic Development of Australia (CEDA) Annual Dinner in Melbourne this week, Mr Lowe backed this view, saying that the RBA must keep a close eye on household balance sheets and avoid Australian borrowers from becoming overleveraged.

The RBA governor said that when the recession hit the United States in 2008, some households found that they had simply borrowed too much.

“What followed was a period of defaults by some, less new borrowing and faster repayment of some debt. The result was a more severe downturn and a more protracted recovery than otherwise would have occurred,” he said.

“Given this and other experiences, we need to pay close attention to household balance sheets here in Australia too.”

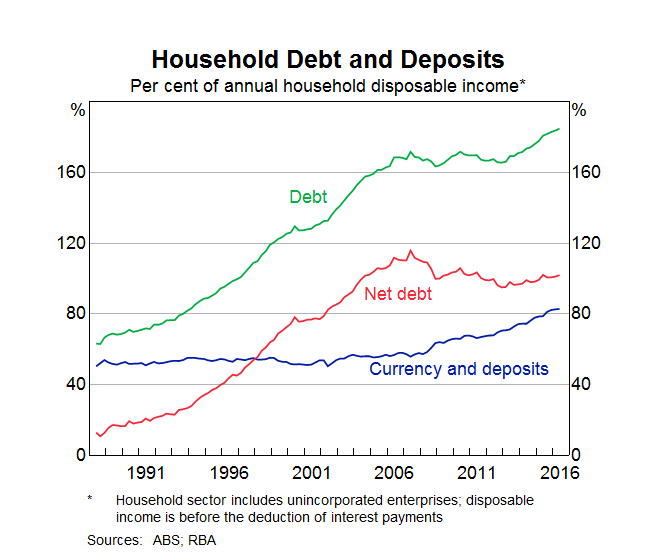

Mr Lowe highlighted that debt levels, relative to income, are high in Australia and are much higher than they once were (see graph below).

Currently, household debt is equivalent to 185 per cent of annual household disposable income, a record high, and up from around 70 per cent in the early 1990s.

“The lower nominal interest rates that followed lower inflation in the 1990s allowed people to borrow more, as did the liberalisation of the financial system,” Mr Lowe explained.

“As a nation, we took advantage of these new opportunities to borrow. As a result, we ended up with both higher levels of debt and higher housing prices.”

Given the high and rising levels of debt, the RBA said it needs to “watch things carefully” and avoid a build-up of financial imbalances in household balance sheets.

“We can never know with certainty exactly what level of debt is sustainable. It depends on income growth, lending standards and asset prices. But it surely must be the case that the higher is the debt, the greater is the risk,” Mr Lowe said.

“Given this, as I said recently when explaining our monetary policy decisions, it is unlikely to be in the public interest, given current projections for the economy, to encourage a noticeable rise in household indebtedness, even if doing so might encourage slightly faster consumption growth in the short term.”

Indeed, the market is increasingly of the expectation that the RBA will hold the cash rate at 1.50 per cent next month, with the RBA Rate Indicator showing there is now only a 5 per cent expectation of a drop to 1.25 per cent on 6 December, down from 12 per cent earlier this month.

[Related: RBA likely to cut rates in 2017: AB]