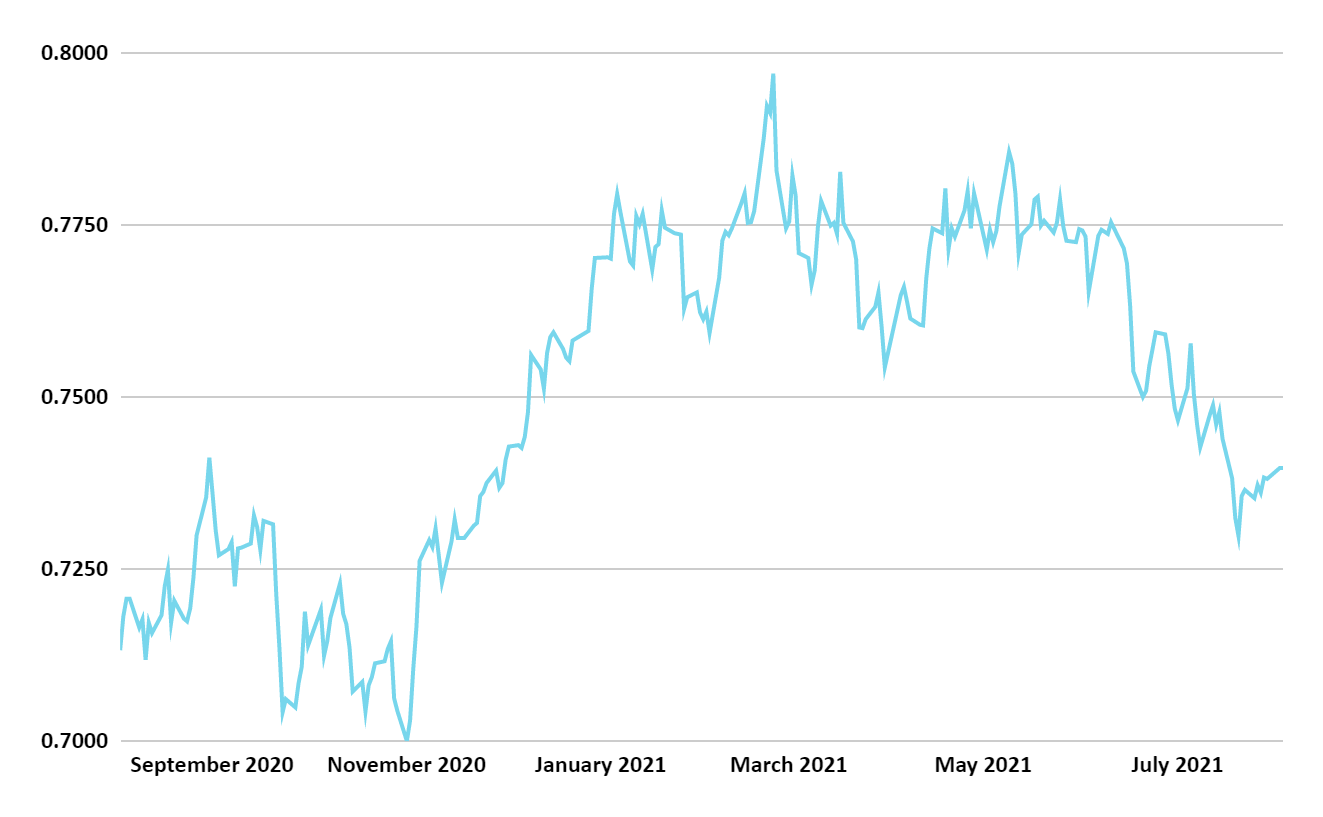

After vacillating between .75 and .78 to the US Dollar (USD) between December 2020 and June this year, the AUD touched an eight-month low in July and has been volatile, hovering below .74 ever since.

There are a number of reasons for this, which have combined to create problems for brokers and their importing and exporting clients who prefer a stable currency.

The first is that any rally in the USD dollar has been paused following dovish signals by Federal Reserve chair Jerome Powell, who said the American job market still had some ground to cover before it would be time to taper bond purchases.

In Australia, the actions of the Reserve Bank of Australia last week (3 August) caught many by surprise as it maintained its current policy stance despite a contraction expected in the Australian economy this quarter.

The growing concern about the spread of the more infectious COVID-19 Delta variant, and the impact of lockdowns on jobs and the Australian economy, may still force the central bank to reverse its previous decision to commence tapering of bond purchases in September. It could also take the view that a lower Australian dollar would be good for our exports and the economy

Another risk to the AUD recovery is the global exposure to the Delta variant.

A delay in the global economic recovery could force a shift in the current optimistic outlook, dampening demand for commodities and the AUD, which has not happened so far.

For exporting and import companies this volatility and the unpredictability of where currency levels will break has created headaches. Hedging plans for the start of the financial year, which were put in place two or three months ago, may have been based on assumptions that are no longer accurate.

Companies that do not have hedging plans in place could be in a worse situation; the currency is low, do they budget at these levels, or do they wait for the currency to be higher?

Take, for example, a shoe importer. The company has the whole financial year to budget for. If the AUD currency goes down to $0.70 and it does not have anything in place to mitigate that risk, then instead of making a 25 per cent gross profit, for example, it could make only 5 per cent - or actually not even make any money this year.

The reality is that no one knows where the currency is going.

The solution for importers and exporters is to match their currency strategy to their business plan.

If I were the CFO of the shoe company, I would be looking at my cashflow forecasts, how much I need to purchase overseas this year, and when and use that to set my budget. Then, I would overlay that with a plan to manage my currency exposure and stick to that plan.

That does not necessarily mean hedging for the full 12 months of the financial year. The shoe importer may have quarterly cycles, or it may have different seasonal impacts during the year (such as times to buy and import summer ranges and winter ranges), and the company needs to budget and hedge according to that commercial rhythm.

While large companies have currency and hedging expertise in-house, smaller exporters and importers often will not.

For these companies, it is critical they make use of counterparties, independent experts in this space who can provide the companies with the advice and protection they need.

When it comes to currency, the cost of not hedging your business bets can be too high, especially at a time when the global pandemic is causing so much uncertainty.

Rick Roache is based in Sydney and is managing director Asia Pacific for Ebury, a global fintech company offering financial solutions built to help SMEs and midcaps manage cross border business more effectively.